Self-insured employers view the cost of specialty drugs as a major challenge in providing health benefits, according to a survey released yesterday by the Midwest Business Group on Health (MBGH).

Cheryl Larson, MBGH’s president and CEO, told Fierce Healthcare that “the new million-dollar treatments approved by the FDA; 30 of our employers said that this is a top threat. And we need to recognize as a coalition that some employers won’t be able to cover these therapies.”

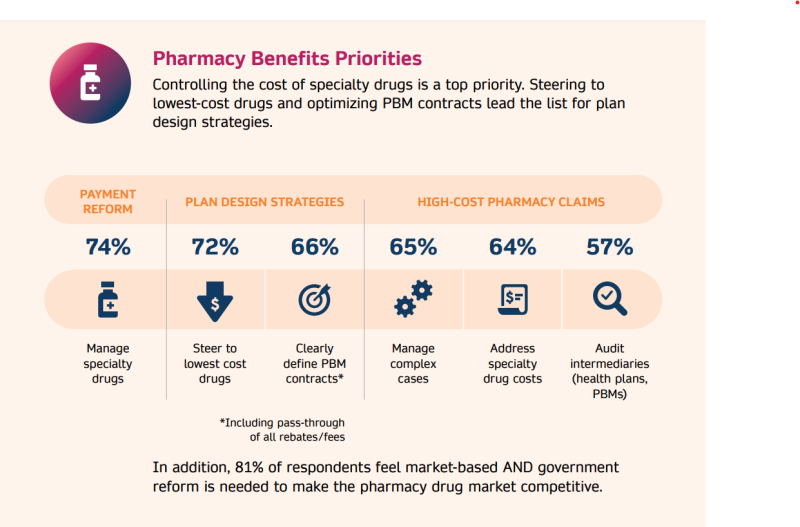

MBGH comprises self-insured employers who provide benefits to over 4 million people, spending about $15 billion per year. Seventy-two percent of survey respondents want to manage specialty pharmacy costs by steering beneficiaries to lower-cost alternatives.

In addition, respondents want to manage specialty drugs through payment reform (74%) and by more optimized pharmacy benefit manager contracts (66%).

MBGH members want clearly defined contracts that “benefit not just the PBM, but that also significantly benefit the employer,” said Larson. “Because in the past, the PBM has been the one that has benefited. We want to make sure that these contracts clarify the role of the PBM. What their responsibilities are. We want to get rid of functions that allow for misaligned incentives.”

Another priority for MBGH respondents: 88% want to make sure that they comply with the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA). That legislation makes self-insured employers the fiduciaries of the benefits they offer workers, meaning that they need to oversee, in a way they needn’t before, the quality and cost-efficiency of the coverage they offer employees or face fines by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that could quickly reach into the millions.

“This is so relevant, because we’ve been talking to our members about fiduciary responsibility for years,” said Larson. “And their consultants tell them, ‘Everything’s fine. You have nothing to worry about.’ Or other entities say it’s fine. It’s not fine. Because in the end, it falls on the employer.”

The government wants information held by the employers’ third-party administrators or PBMs, and the companies “can’t see this data,” said Larson.

“So how can they be fiduciary if they don’t know what the data really says? Unless they have hired a data analytics company, which most large and jumbo employers have, they’re still not seeing the provider contracting, or what the PBM paid to the pharmacy intermediaries for the drug,” she said.

Smaller employers might have problems, Larson added.

“The smaller you are, the harder it is to have an impact,” she said. “So, if you want to have something from a PBM or carrier, they might say, ‘Yes, you can have that.’ But they’re just pushing the balloon in another area because, in the end, they’re not going to make less money.”

Employers are still learning about their obligations under the CAA. For example, Larson said she asked a room of people at a MBGH conference about the legislation.

“There were about 400 people in the room, and I asked, ‘How many of you have complied with the CAA?’ And about half the room raised their hands," she said. "We had some people from larger employers there, and I could see them on the phone with their HR benefits people. Then, they would say, ‘OK. We complied.’ We knew that the two things that they had to mostly comply with were mental health parity and pharmacy benefit.”

Regarding mental health, survey respondents want to:

- Ensure mental health parity (92%)

- Offer no- or low-cost telehealth counseling (74%)

- Train managers about mental health issues (56%)

- Provide flexible work hours so that employees can seek counseling while on the clock (52%)

Another key concern flagged by the survey was hospital transparency concerns, with 80% of respondents saying hospital pricing is unreasonable. In addition, 65% said the same about hospital margins.

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the surveyed employers also argued that market consolidation has not improved the cost or quality of services, and 50% said high-quality hospitals do not necessarily cost more than those providing lower-quality care.