Diabetes patients suffer when their employers move them into high-deductible health plans, increasing the odds that they will need to be rushed to emergency departments for severe hyperglycemia by 25%, a new study shows.

In addition, the odds of this happening increase by 5% for each year an employee’s enrolled in an HDHP, according to a study published today in JAMA Network Open.

Mayo Clinic researchers concluded that “individuals with low income and from minoritized racial and ethnic groups were especially susceptible to the detrimental outcomes of HDHP transition. Thus, HDHP enrollees may be rationing or foregoing necessary care, which is detrimental to their health and ultimately increases the morbidity, mortality, and costs associated with diabetes.”

Those costs are enormous, accounting for 1 in 4 healthcare dollars, according to a study by the American Diabetes Association that also estimates the annual cost of diabetes care and treatment at $327 billion, including $237 billion in direct costs and $90 billion in reduced productivity.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that 37.2 million individuals in the U.S.—11.3% of the population—have diabetes, with 28.7 million having been diagnosed with it and another 8.5 million who do not yet know that they have it.

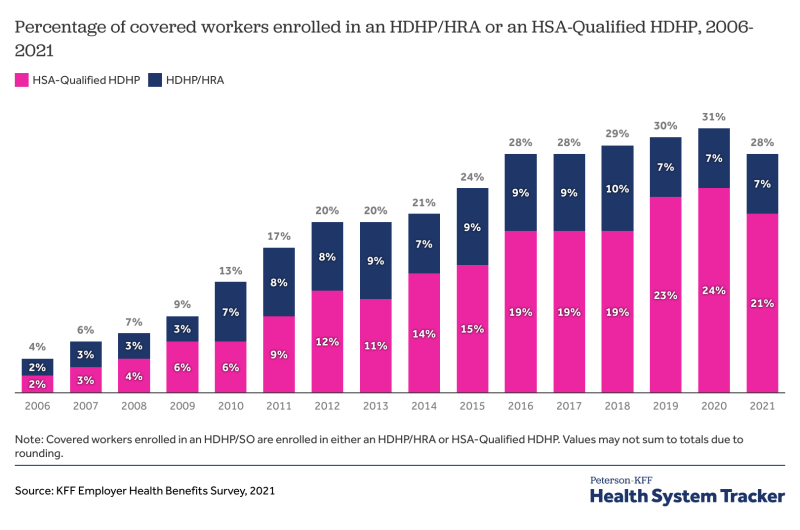

This chart shows how enrollment in HDHPs linked to a health savings account or a health reimbursement arrangement has grown over the years.

The JAMA Network Open study noted that many employers offer a range of healthcare plans, but some only offer HDHPs. Because employees in HDHPs must first pay the cost for healthcare in full through their annual deductible—which can be $1,400 and up for an individual—those with chronic conditions such as diabetes might forego needed preventive and maintenance care that can be provided in a visit to a primary care physician and which is much less costly than care in the ED.

The study focuses on individuals with diabetes whose employers forced them to switch from a non-HDHP to a high-deductible plan. Researchers found that each year of enrollment in an HDHP for individuals with diabetes increased the odds of an ED or hospital visit for hypoglycemia by 2%. Severe-cause dysglycemic occurrences can be avoided through effective glycemic management. That they occurred suggests patients experience gaps in care.

The study said: “When comparing all study years, switching to an HDHP was not associated with increased odds of experiencing at least 1 hypoglycemia-related ED visit or hospitalization … but each year of HDHP enrollment did increase these odds by 2%... In contrast, switching to an HDHP did significantly increase the odds of experiencing at least 1 hyperglycemia-related ED visit or hospitalization … with each year of HDHP enrollment increasing the odds by 5%.”

This might seem contradictory but isn’t, according to the study’s corresponding author, Rozalina G. McCoy, M.D., of the division of community internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic. She and her co-authors looked at the impact of HDHPs in two different ways.

“First: Do people who switch to an HDHP have a higher risk of the outcome compared to those who did not switch? And second, how does the risk of the outcome change the longer a person is enrolled in an HDHP? The thought is that the longer someone is enrolled in an HDHP, the greater their financial burden, the more they may be impacted by the forced switch," she told Fierce Healthcare in an interview.

For hypoglycemia ED visits and hospitalizations, patients who were forced to switch to an HDHP had a similar likelihood of having an ED visit or hospitalization as individuals who didn’t have to switch.

“But, as we followed patients over time, we did see that for those patients who were enrolled multiple years, those later years of HDHP enrollment did result in an increase in hypoglycemia ED visits/hospitalizations,” said McCoy. “I think that these results suggest that we didn’t see an overall impact because many patients in the study didn’t have multiple years in our data, so we only saw the impact during Year 1 of the switch (and there was no immediate impact), but for patients that we were able to follow longer and examine the impact of prolonged HDHP exposure, we did see that each consecutive year in an HDHP increases risk of hypoglycemia ED visit or hospitalization by 2%.”

The data come from 245,055 employees enrolled in an employer-sponsored health plan between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2018, of which 42,326 eventually switched to an HDHP.

“To reduce risks of selection and voluntary bias, we only included individuals whose employers did not offer a choice between HDHP and non-HDHP plans,” the study said.

The enrollees were separated into ethnic and racial categories because Black and Hispanic individuals with diabetes experience hypoglycemia- and hyperglycemia-related ED and hospital visits significantly more often than white patients. In addition, they’re less likely to enroll in health savings accounts, which can offset the costs of healthcare for enrollees.

These realities have not gone unnoticed by employers. Last April, the Northeast Business Group on Health released a guide for employers looking to tackle obesity and diabetes through a racial lens.

The JAMA Network Open study found that the detrimental outcomes caused by HDHP enrollment should encourage employers to offer a variety of benefit packages to workers and provide more transparency about costs in different clinical settings. Often, employees aren’t familiar with the details of the health plans that they sign up for and might focus on the relatively less costly monthly premiums for HDHPs.

Researchers stated that their “findings suggest the need for policy solutions to address health plan-mediated barriers to diabetes care.” For instance, policymakers should consider requiring employers to fund HSAs and to encourage workers with low income to participate and thereby offset the higher costs associated with HDHPs.

They may also want to have employers redesign their HDHPs by including value-based deductible exemptions.

“Some employers and health plans have started to develop value-based insurance designs, such as preventive drug lists, that would encourage patients to use high-value services at a lower cost,” the study said. “In 2019, the Internal Revenue Service has expanded preventative care and chronic disease exemptions to HSA-qualifying deductibles to include diabetes medications (insulin and other glucose-lowering agents, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), retinopathy screening, glucose meters, and hemoglobin A1C testing, which allows these services to be covered by insurance before the full deductible is met.”

Here's more from our conversation with McCoy:

Fierce Healthcare: Could you tell us more about how the data in the study should be interpreted?

Rozalina G. McCoy: These data should be interpreted in the context of other findings for hypoglycemia, namely that patients who were forced to switch to an HDHP were 11% more likely to have documented hypoglycemia compared to patients who didn’t switch, with an additional 5% increase in risk for each consecutive year of HDHP enrollment. The reason for this is that hypoglycemia can be managed without the ED or hospital; a caregiver or bystander can give the patient a carbohydrate-containing food or sugar, or an ambulance can be called and treat the patient on scene without then bringing them to the ED.

So, we think that patients who are forced to switch to an HDHP are more likely to have severe hypoglycemia, but they are rationing medical services and not going to the ED for these events. And for severe hyperglycemia, results are different. Hyperglycemia is likely more susceptible to barriers to medical care, since hyperglycemia occurs when patients with diabetes do not take their diabetes medications/insulin or do not take enough or do not receive needed diabetes education and care to ensure they are managing their disease appropriately, while hypoglycemia occurs when patients either take too much of their medication/insulin or do not eat/ration food. So, we found that forced switch to HDHP results in a 25% increase in ED visits/hospitalizations for hyperglycemia, with an additional 5% increase for each year enrolled in an HDHP.

FH: As you and co-authors spell out in the study, employers began using HDHPs as a way to curtail ever-increasing healthcare costs. What’s the economic rationale for employers to think twice about shifting their workers who have diabetes into an HDHP?

RM: From the economic standpoint, ED visits and hospitalizations for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are very costly and incur high indirect costs because of reduced productivity and time off work. There is also extensive literature showing an association between poor glycemic control (the extreme of which are these ED visits and hospitalizations for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia) and heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, diabetic eye disease, amputations and others.

So, a forced switch to an HDHP will make it harder for people with diabetes to manage their disease, will cause them to experience costly and life-threatening acute complications of diabetes (hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia) and increase the likelihood of them experiencing chronic complications of diabetes and die prematurely. If employers want a healthier and more productive workforce, they need to invest in timely, high-quality diabetes management. And HDHPs are just not conducive to that because they force patients to ration care. And we know that patients don’t ration care that is clinically “low value” (the original intent of HDHPs), but rather care that they deem to be less urgent (care for a chronic disease like diabetes).

FH: What surprised you most about your findings?

RM: Even though I hypothesized that there will be an impact of switching to an HDHP on severe hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, I was struck by just how much, particularly for hyperglycemia. I was somewhat surprised that medication use did not seem to contribute to the difference in risks in hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia (I thought that if patients were rationing healthcare, they would choose medications that are less expensive but are also more prone to hypoglycemia), but I think this reflects the use of manufacturer savings cards to decrease the out-of-pocket cost for medications. Patients in all private health plans are eligible to use those for drugs that have them, both HDHP and non-HDHP, and they decrease the cost share quite a bit.

FH: Is there anything that I neglected to ask that you want healthcare professionals or the public to know about the study?

RM: I think that it’s important to realize the downstream implications of HDHPs. I worry that people are lured by lower premiums without considering the total healthcare expenditures they will face down the road as they actually have to manage their disease. Diabetes care is extremely expensive, and shifting the cost of that on the patient will cause them to ration care. And rationing care in diabetes is dangerous. So, we need to make sure that people understand how HDHPs work, see the total cost of care rather than just the premiums and have the option of a health plan that actually covers their medical needs. HDHPs are fine for healthy people who don’t actually use healthcare, but they are dangerous for people with chronic health needs.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.