Health plans would play a vital role in extending Medicaid benefits to include housing, a possibility that’s gotten a boost from certain initiatives by the Biden administration, according to a Forefront article in Health Affairs.

The author, Dori Glanz Reyneri, a director with consulting company Manatt Health, cited the administration’s willingness to approve pilot programs under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act that would allow Medicaid to provide funding necessary to support housing needs.

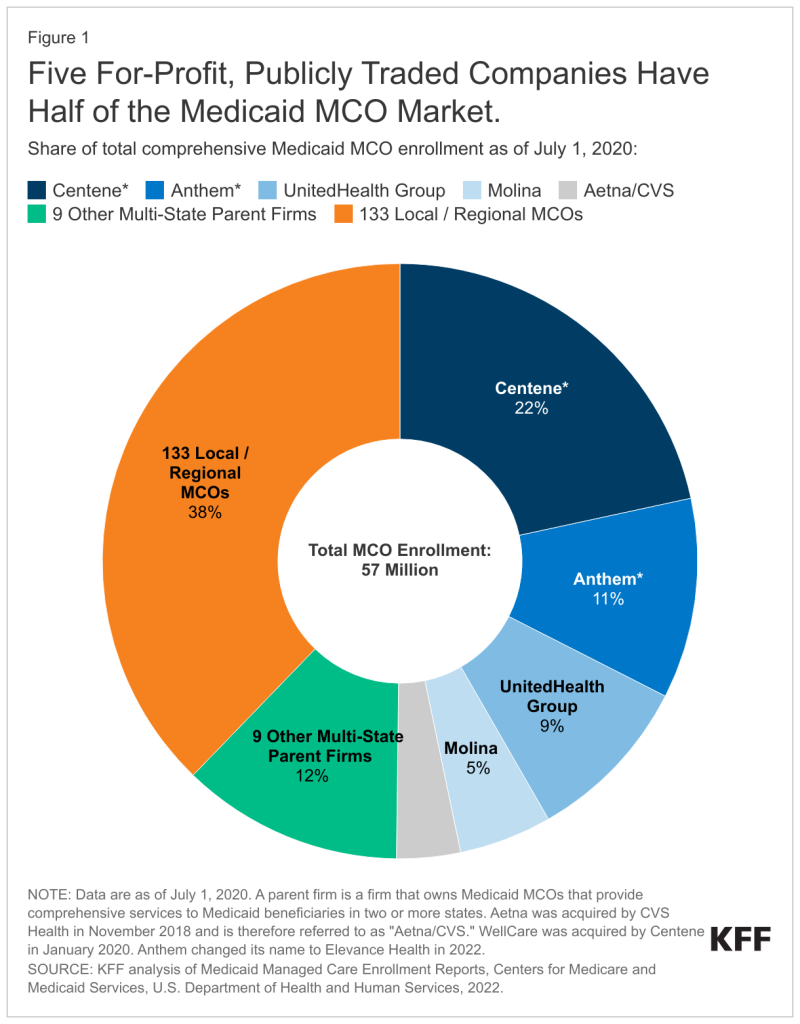

In addition, the administration laid down some ground rules that would let states and health plans offer short-term “support” for housing instead of other services. About 72% of enrollees get their coverage from a health insurer, with five companies cornering about 50% of the market.

This remains very much theoretical, wrote Reyneri, even with the moves by the administration, because all the parts that need to move might not be moving in the same direction. Access to long-term housing falls under the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and HUD rules often would disqualify many Medicaid recipients. For instance, individuals with substance use disorders or those who’ve been recently freed from prison don’t qualify for HUD housing. Other federal housing programs target specific populations such as foster children, veterans and domestic violence survivors.

“The true integration of health and housing worlds is a long-term project,” Reyneri told Fierce Healthcare. “That’s not something that’s going to happen overnight, even in the states that are already doing this. They’re at the beginning of putting those pieces together. Medicaid is doing their thing over there. And the housing agencies and organizations are doing something different with their money over there. Those two worlds are coming together in bits and pieces.”

A lot will depend on how different states choose to approach the idea.

Making Medicaid a major player in housing will require data sharing between the healthcare and housing industries. Here’s where the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will need to expand data auditing beyond Medicaid outcomes and costs but also on the availability of suitable housing of both the short- and long-term variety. Some states have already experimented with this process.

Reyneri’s Health Affairs article cited California, which “is pursuing data sharing across housing support providers, managed care plans, Continuum of Care organizations, and others using Medicaid dollars, including capacity-building and performance-incentive funds, and via state legislation that established a health and human services data exchange framework.”

Reyneri used a term familiar to officials who need to extract funding from different sources to provide public housing: “braiding.” In any effort to make Medicaid a player in housing, braiding would have to enter into it.

“For example, to receive Medicaid funding, providers may have to enroll in the program or contract with multiple managed care plans, screen enrollees for Medicaid eligibility, provide data for service authorizations, manage referrals, code and bill for services delivered, and adhere to other reporting requirements,” Reyneri wrote. “Other programs and funding sources come with their own procedures for eligibility, referral, authorization, and payment.”

Richard Stefanacci, of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that even though the new CMS guidelines make the idea of Medicaid becoming a housing player more viable, the idea will most likely remain just that—an idea—for a long time.

“I’d say a modest chance for happening at best,” said Stefanacci.

Medicaid currently plays a very limited role in housing, mostly through home modifications and tenancy support for seniors and the disabled. He reiterated Reyneri’s point that Section 1115 would require forming partnerships and addressing housing issues, the major one being that there’s not enough housing to go around.

What should managed Medicaid plans do to become part of such a push? “Build partnerships with housing agencies, coordinate referrals and data sharing, connect members to community resources,” said Stefanacci.

Stefanacci cited as a good example the partnership between NewCourtland, a Philadelphia company that provides home healthcare, social services and the state PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly) that established state-of-the-art affordable housing for elderly in one of poorest ZIP codes in the country.

Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., a professor at the University of Southern California, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that a lot of experimentation will be needed to find the best way to blend housing and Medicaid. “Evaluations will be an important component of this experimentation,” Ginsburg said. “An important challenge, which the Forefront piece pointed out, is that federal housing programs’ priorities for which individuals can benefit often do not line up with those Medicaid beneficiaries for whom housing assistance has the largest potential.”

Reyneri told Fierce Healthcare that managed Medicaid housing could be a profitable business niche for health plans. “The payment structure for plans depends on the authority that the state uses to authorize the service,” she said. “But generally, they get paid to deliver the service. It’s a service line. It’s just like any healthcare service that they provide.”

Stefanacci said that “for Medicaid managed care plans, short-term housing assistance for very high-risk members could generate savings that outweigh the upfront costs. If even a small percentage of high-cost cases can avoid one hospitalization through stabilized housing, that could represent significant savings and better outcomes.”

Reyneri said mixing Medicaid and housing is not a new idea. “There’s always been some housing support services,” she said. “What’s different about this is that there would be more people who can qualify. The biggest new service is actually paying for the housing or the rent. That’s new to Medicaid.”