Mental health conditions are the leading cause of maternal mortality, and most pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

A recent survey found that 70% of women say they wish they had known more about postpartum mental health before giving birth, with the number even higher among women of color. Yet as news of worsening maternal health outcomes continue to make waves in the U.S., mental health is often missing from the conversation.

Though screening alone does not improve outcomes, it can help identify conditions early and decrease stigma around mental health. Bodies like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have national guidelines on the recommended frequency of such screenings.

But to date there has been almost no insight into screening practices nationwide. In 2022, the first set of maternal depression screening data became available. Screening in both pregnancy and postpartum was lower than 20%.

Health tech company Komodo Health, which curates a “healthcare map” of de-identified data on 330 million patients, analyzed documented screenings in 2021 at Fierce Healthcare’s request. The data were mostly based on claims information.

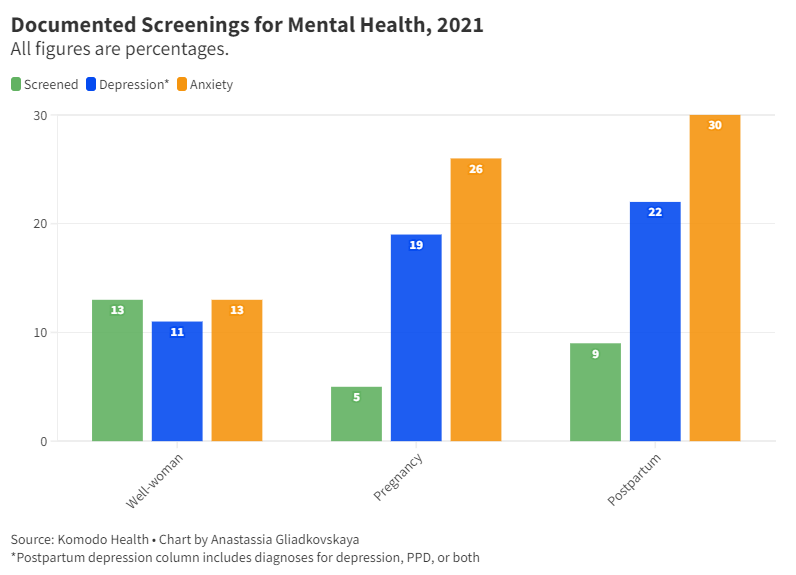

It found that screening for mental health conditions was done more at well-woman visits (13%) than during pregnancy (5%) or postpartum (9%), with the most common age category screened being 65 to 88 years old.

“These screenings are either not being performed routinely in a high volume or it’s just not being documented consistently,” Komodo Medical Director Tabby Khan, M.D., told Fierce Healthcare.

Though screening was higher at well-woman visits, diagnoses were lower: 11% were diagnosed with depression and 13% with anxiety. Conversely, of the 5% of patients with a documented screening during pregnancy, 19% were diagnosed with depression and 26% with anxiety. (Analysis relied on procedure codes for a birth visit, including a vaginal delivery and a C-section, or documentation of delivery with a diagnosis code, including any pertinent complications.)

Diagnoses were even more common postpartum, defined as the nine months after a birth event. Of the 9% with a documented screening, 22% of patients were diagnosed with depression, postpartum depression or both, and 30% were diagnosed with anxiety.

“We can't act on this unless we know what’s wrong,” Khan said. “There needs to be some type of incentive for providers to track this.”

'Zero infrastructure' to support guidelines

OBs are not typically trained on mental health. The field of reproductive psychiatry is still considered relatively new, and doctors can be reluctant to treat mental health conditions in pregnant patients.

In May, ACOG updated its voluntary provider guidance to recommend screening for perinatal depression and anxiety at least three times: in the prenatal period, later in pregnancy and postpartum. The update also covered other mental health conditions as well as follow-up options after a positive screen. Prior to the change, ACOG recommended screening for perinatal depression at least once, the organization said.

“Many obstetrician-gynecologists are not trained to treat all mental health conditions,” Christopher Zahn, M.D., interim CEO and chief of clinical practice and health equity and quality at ACOG, told Fierce Healthcare. The new guidance and other ACOG resources will “hopefully build confidence among obstetrician-gynecologists in addressing perinatal mental health with patients and provide suggestions on collaborative care and referrals.”

But some providers argue the recommendations are not enough. “While these guidelines are definitely a step in the right direction and are consistent with the compelling data around prevalence, there is zero infrastructure to support this,” Sipra Laddha, M.D., co-founder of LunaJoy, a mental health startup focused on women, told Fierce Healthcare. “Boots on the ground working with many OBs in our integrations, most are not consistently following even the old guidelines.”

ACOG guidance is designed as an educational resource, Zahn said. “With regard to implementation, it is a multifaceted process of which guidance is just one part," he noted.

OBs may lack the time and resources to screen, per Laddha. Referrals add another challenge. ACOG recommends OBs initiate pharmacotherapy, refer patients to behavioral health resources or both. But mental health treatment is often cash-based and expensive, and wait times for patients are said to be getting worse. “We don't want a positive lab value or screening in the EMR unless we can do something about it,” Laddha said.

Integrating services with collaborative care

A 2022 survey, claiming to be the first of its kind, reached 118 OB-GYN hospitalists and found that screening practices were “inconsistent and potentially lacking.” About 66% screened in the labor and delivery or antepartum units, while half screened in the postpartum unit. A quarter screened in OB emergency department encounters. Fewer than half screened during a hospital admission if a patient self-reported concerns.

Northwell Health launched a behavioral health collaborative care model at several ambulatory OB practices during the pandemic. Building it out took years. Several rounds of analyzing screening protocols and data led providers to find high rates of depression among new mothers.

“That's where persistence for your patients’ health is vital for this situation,” Stephanie McNally, director of OB-GYN services at Northwell’s Katz Institute for Women's Health, told Fierce Healthcare. “If we’re not asking the question, are they suffering in silence?”

Northwell’s OB-GYN practices screen for mental health three times—in the first trimester, mid-pregnancy and postpartum. Two Northwell hospitals screen four times. Referrals for treatment had previously been limited to the community or Northwell’s perinatal center. With the new model, more than 200 patients were seen by a behavioral health counselor in the first two years at a single OB practice. The program then expanded to two more locations.

Catherine Jacklin is a behavioral health counselor and care manager offering remote psychotherapeutic services and consulting with a supervising reproductive psychiatrist. Instead of waiting for patients who screen positive to call her, Jacklin reaches out to patients first—a more effective way to reach people, she says.

“I think that really allows us to support a lot more people than we would’ve been able to,” Jacklin told Fierce Healthcare. Keeping flexible hours and a dedicated phone number for when patients call helps remove barriers to care, she added. Appointments are documented in Northwell’s care management platform.

Being remote also helps immensely with access, especially for a population busy with pregnancy or childcare: “That’s actually something that we’ve found to be just incredibly helpful for new moms," she said.

So far, patients are improving, according to George Alvarado, M.D., medical director of behavioral health at Northwell Health Solutions. “Docs really like this model,” he told Fierce Healthcare. “It's not hard to sell.”

If demand outgrows capacity, Northwell would likely outsource behavioral health services, Alvarado said. For providers who may not have the budget to do so, he suggested working with local clinics to coordinate behavioral care. In addition, some states, like Massachusetts and New York, offer free programs for physicians to get a phone consultation with a psychiatrist.

The right stakeholders need to be involved to do this work, including leaders across departments, McNally said. Her team works with the finance department to carve out behavioral services in the budget. Though Northwell’s model is remote, which means fewer overhead costs, a collaborative care model may ultimately not be profitable. Even if you break even, that’s a win, McNally believes: “This is not about profit, this is about what’s good for the community.”

How payers fit in

California is among the few states requiring screening at least once during pregnancy and once postpartum by law. But some payers go further. Blue Shield of California recommends providers screen once during the first prenatal visit, at least once each during the second and third trimesters and multiple times postpartum.

The plan creates provider communication to emphasize the importance of screening and includes the language in its provider manuals and new provider orientation. It also monitors screening and follow-up rates quarterly and annually, meeting with providers lagging behind to help increase their rates.

The plan also encourages Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) screenings, which look for trauma in children or adults who experienced trauma as kids. “It’s very important,” Gi Villavicencio, a program manager at the plan’s behavioral health department, told Fierce Healthcare. ACEs go hand-in-hand with maternal mental health: “That gives you a preview of their childhood.”

Managed care plans have a big role to play for Medicaid beneficiaries, said David Bond, director for behavioral health at Blue Shield of California. For high-risk pregnancies, a nurse and care manager are assigned to help coordinate care, schedule appointments and offer financial resources. “It’s the plan’s responsibility to make sure that members have access to the care that they need,” Bond said.

If someone screens positive, providers should submit a code to Blue Shield indicating so as well as a follow-up plan. They can also use a provided referral form to send patients to the plan’s behavioral health services team. Additionally, a social services team helps manage social needs and refer members to community resources.

Access to mental health support should never require a prior authorization, Bond stressed. “If you loop in your managed care plan then they can make sure your care is coordinated,” he said.