The highly infectious and evasive BQ.1.1 variant not only has a foothold in the U.S., it may have established that foothold weeks ago. The data on the variant have prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to redo previous weeks’ variants tracking charts.

“It’s been hiding in plain sight,” Kevin Kavanagh, M.D., founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA, told Fierce Healthcare.

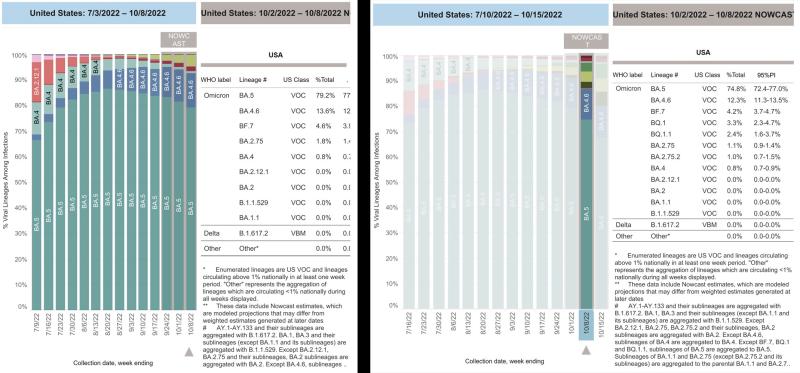

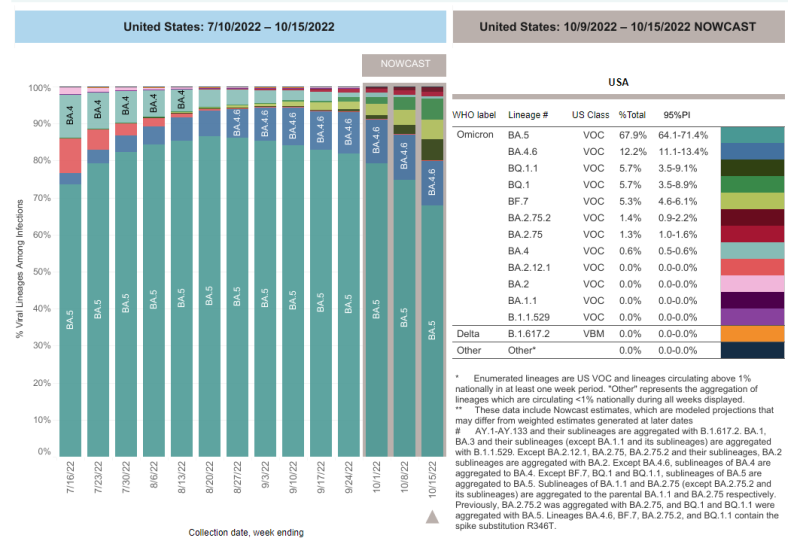

The charts below tell the story. The left shows the first version of CDC tracking data for the week ending Oct. 8, where BQ.1.1 (and its cousin, BQ.1) don’t even appear. The CDC had grouped those data under the BA.5 label, which has been the most dominant subvariant of omicron since early July.

After examining additional data, the CDC this week reconfigured the chart to show BQ 1.1. accounting for 2.4% of new cases of COVID-19 for the week ending Oct. 8 and BQ.1 accounting for 3.3%.

Now look at the chart for the week ending Oct. 15. Both variants now account for 5.7% of new COVID-19 cases in the U.S.

Kavanagh said BQ.1.1 “appears to be doubling every week. Data from CDC appears delayed in being posted on this variant. Once it became apparent in the last few weeks that the variant is having a significant impact, the data were separated.”

As far as his patient advocacy concerns, Kavanagh added that “this underscores the importance of obtaining the bivalent BA.5 booster. For most individuals, the benefits of the booster far outweigh risks.” The take-up of the latest bivalent vaccine has been lackluster, with fewer than 5% of eligible Americans getting inoculated, according to the CDC.

Despite concern about what has become known as the splintering of omicron into subvariants and sub-subvariants (Kavanagh called BQ 1.1 the great-grandchild of BA.5), almost all experts agree that the U.S. will not see the levels of hospitalizations and deaths that occurred in the fall and winter of 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 in the 2022‑23 season.

The public, for the most part, considers the pandemic over, as daily deaths and hospitalization rates plummet, according to the CDC. The Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center records that the seven-day moving average for deaths as of today is 344; for new cases, 35,747.

President Joe Biden last month declared the pandemic over but added that we need to continue to keep an eye on the always unpredictable SARS-CoV-2. The president last Thursday extended the public health emergency for COVID-19 through Jan. 11. That means, among other things, that COVID-19 tests and vaccines will still be free, pushing back the long-term goal of shifting costs for those to health insurance plans.

For now, BQ.1.1 concerns health officials the most, but others wait in the wing. Yunlong Richard Cao, an immunologist at Peking University in Beijing, tweeted that “XBB is currently the most antibody-evasive strain tested, and BR.2, BM.1.1.1, CA.1 are more immune evasive than BA.2.75.2 and BQ.1.1.”

Cornelius Roemer, a physicist major at Cambridge University who closely tracks variants, predicted on Twitter that there will be another COVID-19 “variant wave in Europe and North America before the end of November.” Speaking about Great Britain, Roemer adds that BQ.1.1’s “relative share has kept more than doubling every week. It has taken just 19 days to grow 8-fold from 5 sequences to 200 sequences.”

Eric Topol, M.D., founder of the Scripps Translational Institute, tweeted last week that “XBB and BQ.1.1 are 2 of the most important variants [to] watch right now.” Topol also notes that Germany, France and Belgium are experiencing waves of BQ.1.1

Vaccines and treatments keep us safe, for the most part. Hope abounds that COVID-19 will become like the flu: potentially dangerous, especially for vulnerable groups like the very young or old, but something society can live with.

Tom Peacock, a virologist at Imperial College London, told Stat that the splintering of omicron does make SARS-CoV-2 in some ways more like influenza, but a speeded up version. “It’s a little bit like what we would expect to see over a couple years of flu, but crammed into about three months with SARS-CoV-2,” Peacock tells Stat. Peacock said that it’s telling that we’re facing subvariants of omicron rather than totally new variants, an indication that though different subvariants might spring up in different parts of the globe, they share a common enemy: the immunity people have gotten through vaccines and/or prior infection.

Some of the therapies developed for earlier iterations of SARS-CoV-2 don’t work against the newer subvariants. For instance, the Food and Drug Administration warned last week that Evusheld for immunocompromised individuals can’t protect them from the subvariants.

Kavanagh suggested that it might be time to reconfigure variant grouping methods. “With different lineages developing similar mutations and the myriad of concerning mutations which are having an impact on viral infectivity and severity, one may need to consider a different method of classification, such as using levels of variant mutations,” he said. “A Level 4 Variant would have 4 mutations of concern and a Level 6, six mutations. This may produce a more rapid flagging of variants of concern rather than waiting for data regarding the impact of specific lineages.”