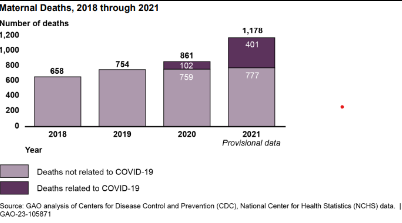

Pregnancy-related deaths soared nearly 80% since 2018, driven by COVID-19 and disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic women, according to a report (PDF) from the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GAO researchers found that “pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to experience pregnancy complications, severe illness, or death. Research also shows racial and ethnic disparities in maternal deaths. For example, Black or African-American (not Hispanic or Latina) women experienced maternal death at a rate 2.5 times higher than White (not Hispanic or Latina) women in 2018 and 2019.”

COVID-19 was a factor in 1,178 maternal deaths last year. In addition, the percentage of preterm and low-birthweight babies also went up for the first time in years. The report states that “the rates of preterm and low birthweight births were significantly higher for infants born to women with COVID-19 during pregnancy (12.2 percent and 9.0 percent, respectively) compared with those without COVID-19 (9.9 percent and 7.9 percent, respectively).”

Carolyn Yocom, a director at the GAO, told Fierce Healthcare that “all of the deaths related to pregnancy or childbirth related conditions, or conditions made worse by pregnancy/childbirth, COVID-19 was listed as a contributing factor for one-fourth of these outcomes.”

More women reported symptoms of depression while pregnant or postpartum, according to the report. Estimated rates of depression symptoms had been rising from 2016 to 2019 and continued to increase into 2020, the first year of the pandemic.

“Pregnancy is a period of mental risk more so than nonpregnant times in a person’s life,” Karen Tabb Dina, Ph.D., a maternal health researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, told Fierce Healthcare. “To experience mental health problems such as depression, suicide ideation, anxiety, panic—these happen disproportionately to pregnant people.

“And now we have COVID-19 to add to our mortality pregnancy crisis. … And you won’t see that ending anytime soon because we are still living this collective trauma as a society. We’re still in COVID-19. We haven’t completely let up in terms of our restrictions. In terms of how difficult it is to be able to practice medicine.”

Tabb Dean says that many providers dealing with pregnant patients who exhibit mental health problems can access a program called Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs. Access programs are in 20 states and through them providers who are dealing with pregnant women who are showing signs of depression and/or suicidal ideation, can get help in how to care for those patients.

The average number of monthly maternal deaths was 55 in 2018 and 63 in 2019. Then came COVID-19.

“During the pandemic, from January 2020 through December 2021, the number of monthly maternal deaths averaged 85 deaths, and peaked in late summer of 2021,” the report found. “The number of maternal deaths in August (155 deaths) and September (173 deaths) of 2021 was higher compared to that of prior months, according to our analysis of CDC data."

CDC noted that the delta variant became the predominant COVID-19 variant in the U.S. in July 2021, and the risk of death for pregnant women was more than three times greater during this time (June 27, 2021, through Dec. 25, 2021) as compared with previous months.

While the omicron variant’s infectiousness led to it killing more people overall than delta, delta is more lethal, said medical experts.

The report noted that social determinants of health also contributed to the spike in pregnancy-related deaths. It cites lower education, exposure to pollution, lack of access to care, being uninsured or on Medicaid and chronic health conditions as factors in pregnancy-related deaths.

Yocom says that “disparities in outcomes were increasing already before COVID-19 became a factor. So, that would suggest that addressing disparities in health care is necessary to bring the death rate down.”

Racism is also a factor that contributes to worsened maternal health outcomes. “For example, chronic stress associated with racism can cause physiological changes and adverse health conditions,” the report states.

Discrimination within the healthcare system can curtail communication between providers and patients.

“For example, pregnant women may be reluctant to ask questions about their condition if they faced discrimination from their provider,” the report states. “In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted racial and ethnic health disparities. For example, among COVID-19 cases with known race and ethnicity reported to CDC, Hispanic persons have generally had a higher rate of cases throughout the pandemic as compared with non-Hispanic persons.”