Pharmaceutical manufacturers surmise that President Joe Biden’s Medicare drug price negotiation program, a provision within the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), will financially incentivize companies to delay launches of lifesaving cancer drugs, but new research says that belief is mistaken.

Small-molecule drugs, in theory, are under the biggest spotlight from the price negotiation program because Medicare’s imposed prices would take effect as soon as nine years after Food and Drug Administration approval, compared to 13 years for other drugs. This could cause pharma companies to delay drug launches to maximize revenues and ensure higher earnings before that threshold is reached. Authors of "Will Medicare Price Negotiation Delay Cancer-Drug Launches?" in The New England Journal of Medicine said that approach could be inconsequential, if not financially damaging.

“In addition to the obvious ethical and reputational concerns from delaying patient access to effective treatments, it will rarely be financially sensible for any firm to incur the cost of clinical trials and then deliberately delay the FDA approval of its product as a response to the IRA,” the study said.

Genentech—a R&D biotechnology company owned by Roche Group—CEO Alexander Hardy told Fierce Pharma in July that he worried the IRA would have “unintended consequences” on small-molecule drugs. Just one month later, he warned that Genentech may slow research for ovarian cancer treatments targeting smaller populations to make sure drugs treating diseases for larger patient populations would be released first, Stat reported.

“Roche’s claim is that delaying the ovarian cancer launch would allow it nine years of Medicare sales for both ovarian and prostate cancer before negotiated prices take effect,” the study said. “By contrast, pursuing a traditional, sequential approval strategy would allow for nine years of Medicare sales at monopoly prices for ovarian cancer but only six years for prostate cancer, which has a higher prevalence.” This approach delays completed trials for prostate cancer by three years.

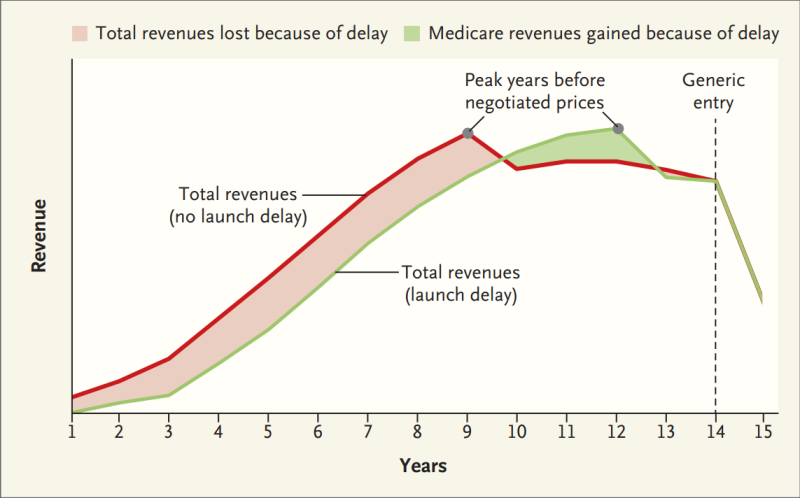

The authors said delaying the drug’s launch will not result in more revenue for its cancer drug camonsertib. While the drug’s revenue life span may be extended and its revenue may peak later in its life cycle, it is offset by less revenue for the first nine years.

In fact, analysis of a delayed ovarian cancer drug versus the same drug released immediately resulted in 11% less lifetime revenue for the drug company. Losses outweigh the benefits in other scenarios as well. Those scenarios include a range of discount rates, payer mixes and revenue-growth trajectories that are more favorable to delayed entry into the market and a prostate cancer market 15 times the size of the ovarian cancer market with 75% reductions in Medicare sales after price negotiations.

“Revenue losses would be even greater if the firm also delayed the launch of the drug internationally, which may be expected given the conventional wisdom that global revenue can be maximized by launching at higher prices in the United States before negotiating with thriftier foreign governments,” the study added.

It noted delaying a drug is also risky because only 15% of drugs in phase 2 studies are approved by the FDA, and many drugs don’t earn most of their revenue from Medicare. A delayed launch would cut off revenues from all other public, private and off-label uses normally at a pharmaceutical company’s disposal. Delaying a launch could also forgo a company’s competitive advantage should a rival release a similar product first.

Other risks include the drug companies potentially wasting valuable patent time without a drug on the market and a high-level worry that guaranteed money now is inherently more valuable than potential funds in several years.

The analysis concedes that these factors may not apply in monopoly markets, where modified drug formulations would not be released until older formulations are nearing the end of their patent lives.