Despite dwindling infection and death rates, COVID-19 won’t ever entirely go away; many experts say it’s endemic. Then, there are the challenges presented by long COVID, including the stigma associated with the condition.

A recent study in PLOS One offers a new tool that helps measure stigma that might discourage patients from getting care for long COVID. In addition, researchers with the University of Southampton, in the United Kingdom, found that individuals who’ve been diagnosed with long COVID are—perhaps counterintuitively—more likely to feel stigmatized than those who haven’t been diagnosed.

“The reason is not clear,” the study said. “It may be that this group were exposed to more stereotyping or dismissal of their experience during their journey to obtaining a clinical diagnosis compared to those with no clinical diagnosis who perhaps had less interaction with services and others about their long COVID. It may be that their long COVID is more severe in nature making it more visible to others and/or more impactful in limiting everyday activities.”

There are no generally agreed-upon best practices for diagnosing and treating long COVID. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that “people may have a wide variety of symptoms that could come from other health problems. This can make it difficult for healthcare providers to recognize post-COVID conditions.”

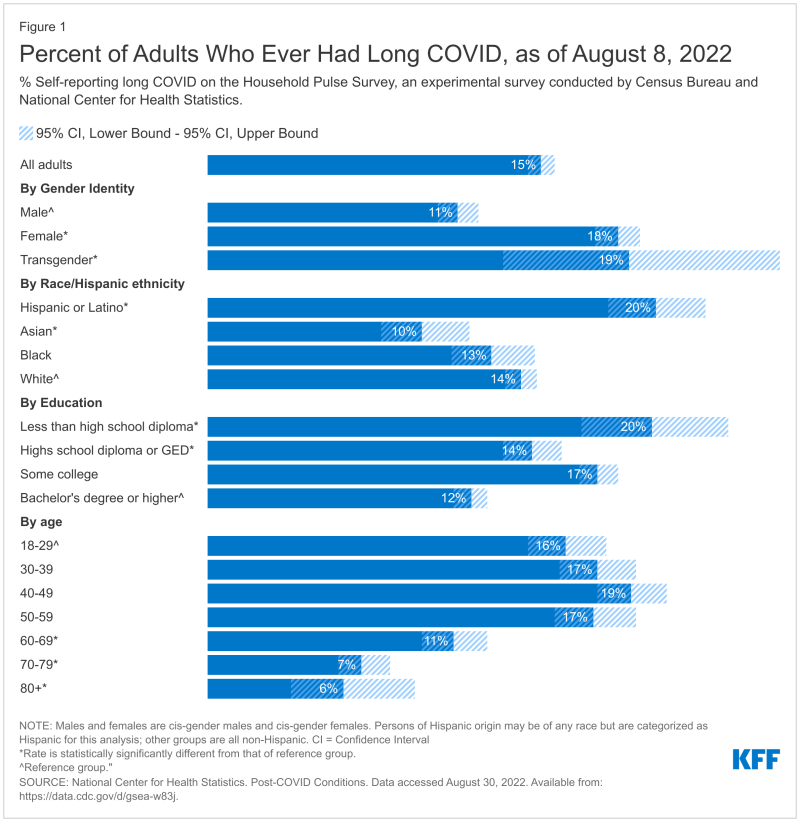

Long COVID is described as having symptoms of COVID-19 four weeks or more after initial infection. Forty percent of adults in the U.S. say that they’ve had COVID-19, according to data from the CDC, with 19% of them suffering from continued long COVID symptoms.

In September, Richard Stefanacci, chief medical officer at the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University, told Fierce Healthcare that health plans and employers won’t put long COVID on their radars because of these unknowns. Lately, though, Stefanacci has noticed a shift in attitude, as payers begin to pay more attention.

“And it will continue to evolve as more information comes out,” he said.

Stefanacci advised payers and providers to “keep up to date regarding findings on diagnosis and treatment. Also, remember ‘do no harm.' So, take care to balance diagnostic work-up and treatments against potential risks.”

Michael Millenson, an internationally known expert on quality and care, told Fierce Healthcare that health plans should consider forming advisory panels that include patients with long COVID.

“Paid patient advisory groups are usually thought of as something that hospitals and other providers do,” said Millenson. “But in this case, I think it’d be really worthwhile for health plans to have an advisory group and invite in some patients because they need that kind of input. You’re not talking about something with clear clinical indicators. You’re talking about something that’s amorphous and developing, and they need to keep their finger on the pulse of what’s happening with patients.”

In the PLOS One study, researchers collected data from a survey of 966 individuals in November 2021 in which they responded to 13 questions designed to categorize three types of stigmas. These include enacted stigma, where individuals were treated unfairly because of long COVID; internalized stigma, where individuals felt ashamed; and anticipated stigma, where individuals expect to be treated poorly because of their condition.

“Overall, 95% of respondents experienced at least one type of stigma ‘sometimes’, with 76% experiencing it ‘often, or ‘always’,” the study found.

Marija Pantelic, Ph.D., a lecturer in public health at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, led the effort to develop the survey. “There have been countless anecdotal reports of the stigma, dismissal and discrimination faced by people living with long COVID,” Pantelic said in a press release. “This study was the first to empirically measure this stigma and estimate prevalence. We were shocked to see just how prevalent it is, but the findings also empower us to do something about it. With the stigma questionnaire we developed, we can measure changes over time and the effectiveness of urgently needed anti-stigma interventions.”

Pantelic noted how stigma can cause poor outcomes for other long-term health conditions, such as asthma, depression and HIV. Fear of stigma drives “people away from health services and other support, which over time has detrimental consequences on people’s physical and mental health.”

There’s a danger that long COVID might be considered to be more of a psychological than a physiological problem, said Stefanacci.

“Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, Lyme disease, obesity and even Alzheimer’s dementia—all have gone a long course to be more clearly diagnosed and treated. Although for all these conditions we still have a very long way to go," he said.

Everything listed above, said Stefanacci, had at one time or another been considered psychological or self-inflicted or simply the result of aging until they were recognized as diseases that could be diagnosed and treated.

“Long COVID is just at the beginning of this long journey although hopefully we can learn from past mistakes in speeding up our learning," he said.

The University of Southampton researchers developed a tool they call the Long Covid Stigma Scale (LCSS), and the study notes that other scales have been created to measure acute COVID-19 infection or risk of such infection. However, “the stigma associated with long COVID is unique, requiring its own measurement tool.”

Researchers found that 63% of respondents had experienced stigma, such as people that they care about suddenly not interacting with them. In addition, 91% said that they expected to experience stigma, often in the form of people not considering long COVID to be real. Eighty-six percent felt embarrassed and abnormal compared to people who don’t have long COVID.

Millenson said that long COVID “threatens not only the quality of life but perhaps the quantity of life. And the most important thing is to listen very closely to the patients.”

He noted that some stakeholders have attempted to become much more patient-centered in recent years. “And in this case, patient-centered means ongoing listening. It doesn’t just mean a nice 800 number.”

Long COVID also puts physicians in a tough spot, said Millenson.

“It’s difficult for the doctors because doctors want to feel that they can do something to help,” said Millenson. “And it’s very difficult to know that they may or may not be able to.”

Physicians need to read up on long COVID, and not just the medical literature. “Read some of the patient testimonials, because this really requires an understanding of the psychological impact on patients and the necessity to listen to patients, as well as what the medical literature says,” said Millenson. “You’re dealing with a chronic disease whose natural course is not yet known and whose most severe impacts are grim.”

Millenson noted that there are some long COVID centers, but not many. Health plans should consider creating more. “The health plans, by setting up these kinds of resources, are supporting doctors. And I think it’s so important for health plans to be able to support the physicians with resources, with knowledge.”