The scope of coverage for fertility treatments might expand in the next few years because some employers believe those benefits can be folded into efforts to enhance diversity, equality and inclusion.

However, economic forces such as inflation might encourage keeping such coverage a hit-or-miss proposition, as has been the case historically, depending on what an employer wants to pay for and what regulations states will enforce, according to Jeff Levin-Scherz, M.D., the population health leader for health and benefits in North America at Willis Towers Watson.

“A lot of employers are thinking about fertility treatment as one of the diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives they make,” Levin-Scherz told Fierce Healthcare. “Offering better fertility service might be beneficial for women in the workplace.”

In addition, paying more up-front means paying less for poor outcomes. Premature births would be less likely.

"If you have more generous benefits, you’re more willing to do single embryo implantation so an employee would be less likely to have to tell the fertility doctor, ‘Please, please put many, many fertilized eggs in me,'" said Levin-Scherz. That’s a leading cause of twins and triplets, which can lead to worse outcomes because they’re more likely to be premature.

It’s expensive. According to the website verywellfamily, the average cost for a frozen embryo transfer ranges from $3,000 to $5,000. If done via an egg donor, the cost jumps to $25,000 to $30,000 for one cycle.

Employers and health insurance plans have historically argued that the decision to go forward with the procedure constitutes a lifestyle choice, and not a medical problem, and should therefore not be a covered benefit.

A 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation report says that “some states mandate coverage of at least some kind of infertility treatment in policies sold through the individual market or small group market or both. State mandates vary considerably. Some apply only to certain kinds of health insurance policies, for example, HMOs. Others specify certain types of infertility treatment, such as IVF, that must be, or not be, covered under the mandate.”

A report issued by the National Conference of State Legislatures issued in March 2021 found that only 15 states require insurance to cover fertility treatments.

Even one of the most comprehensive insurance coverage plans, the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), skimps when it comes to fertility treatment. Government Executive, a publication geared toward government employees, reported in August that “the program only requires insurance carriers to cover the cost of diagnosis and treatment of infertility, leaving many gaps for federal workers seeking to access assisted reproductive technology to get pregnant.”

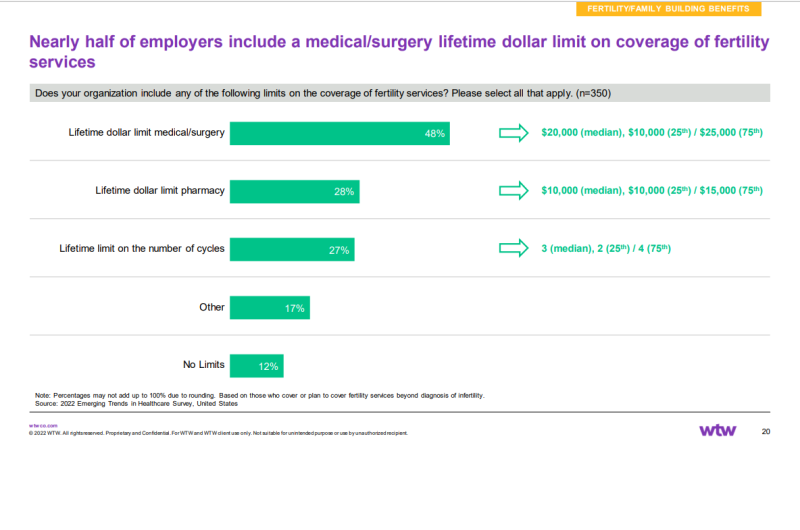

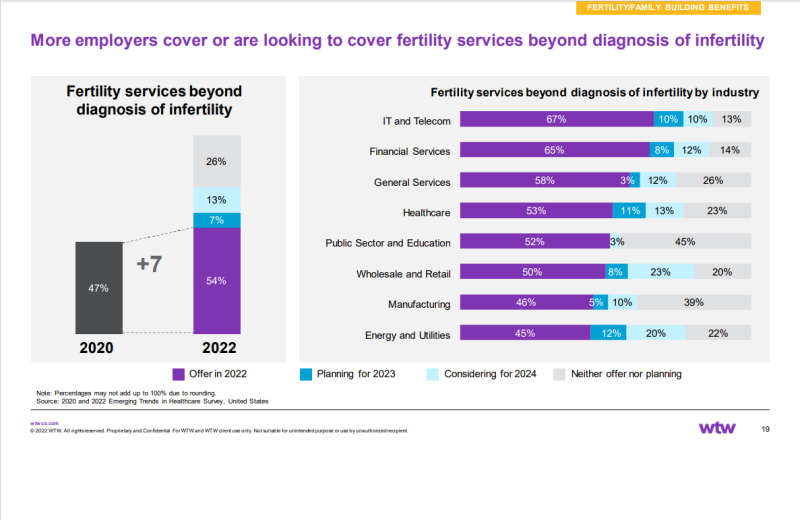

Levin-Scherz said that “fertility coverage is a little bit more common than people might think. The last time we did surveys on it—which was not that long ago—we found that over half of employers in 2022 reported that they did cover some fertility services beyond just sort of being diagnosed with infertility. So, they were covering at least some fertility services. And that was 54%. Most of them had a lifetime limit. The mean and median were both around $20,000.”

Employers aren’t the only stakeholders involved, though. As Levin-Scherz points out, about two-thirds of workers are covered by employers who are self-insured, and those employers decide what kind of fertility treatments to offer, if any.

For employers who aren’t self-insured, states also have a say. “There are regulatory differences from state to state,” said Levin-Scherz. “And those differences from state-to-state are applicable to a fully insured health plan. So, if the employer is writing a check to the health plan … then those are regulated by each state and may differ dramatically from state to state.”

Peter Kongstvedt, M.D., is a nationally recognized authority on the healthcare industry and a senior health policy faculty member in the Department of Health Administration and Policy at George Mason University. “I think it’s going to end up as a state-mandated benefit, at least for insured businesses, and hit or miss for self-funded,” he told Fierce Healthcare.

Levin-Scherz says contradictory elements will influence decisions.

“The tighter labor market which encourages employers to offer new benefits … to distinguish themselves and make their benefit plan more attractive; and how expensive everything else in healthcare gets, which makes employers reluctant to offer new benefits.”

Government Executive reported that although many lawmakers know that fertility treatments are expensive “their inclusion in insurance coverage often has knock-on effects that lower costs in other areas of health care, alleviating conditions like depression, stress and anxiety.”

One thing that will not figure into the equation will be the link reported in some studies between COVID-19 and male infertility, said Levin-Scherz.

“To the extent that COVID might be affecting male fertility, right now there are no specific medical therapies not that I know of that would change that,” Levin-Scherz said. “So, for instance, if an employer said, ‘Oh, we’re going to be really generous with male infertility coverage’, I don’t know that there are things doctors could do for a man [struggling with] infertility which is suspected to be due to COVID.”