Insurers find themselves in the position of needing to say "yes" or "no" to GLP-1 drugs as more people seek them for weight loss.

Ozempic, estimated to cost about $10,000 a year per person, and others in this class could put significant financial strain on payers as demand grows. Other drugs on the market such as Mounjaro (tirzepatide), which was approved for treating Type 2 diabetes but also seems to help with weight loss, could also see greater interest.

Ceci Connolly, president and CEO of the Alliance for Community Health Plans, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that “given some alarming adverse events and the steep price tag, ACHP and our member companies are focused on ensuring prescribing decisions are based on science as well as on providing patients with the best care possible.”

David Allen, a spokesperson for AHIP, echoed Connolly in an email to Fierce Healthcare, saying that insurers routinely review treatments for obesity, including lifestyle changes and nutrition counseling.

Allen said evidence indicates that the GLP-1 drugs do indeed help people lose weight. However, “the evidence is still evolving related to how these medications may impact complications related to obesity such as heart disease and diabetes.”

The Pharmaceutical Strategies Group (PSG), a pharmaceutical management consulting company, surveyed 180 benefits executives representing health plans, employers and unions and found that these drugs are a major concern.

“The drugs could produce huge benefits for people with obesity but also present a major cost challenge given the large percentage of the population that is eligible for them,” the report said. “Recognizing the choices and challenges plans are beginning to face in this area, we asked respondents a series of questions about their perspectives and approaches related to weight loss medications.”

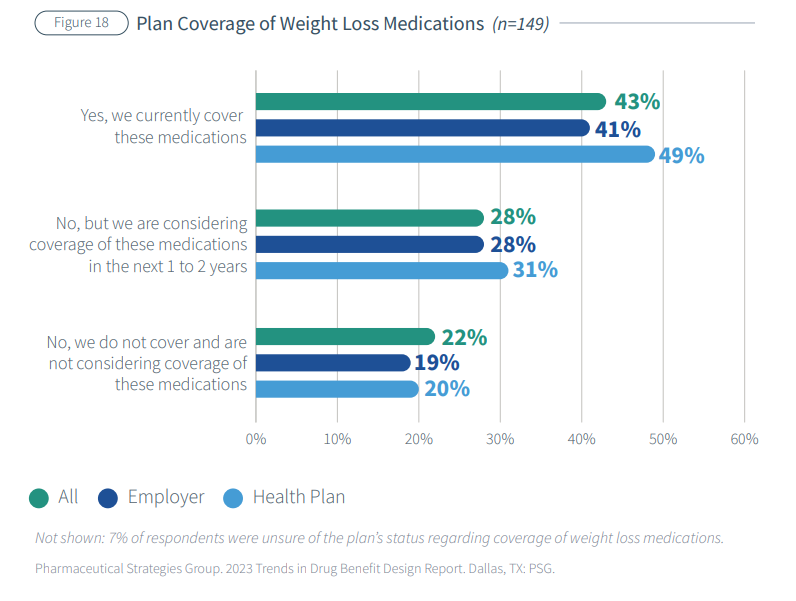

Respondents differed on whether to consider weight loss a lifestyle issue or a chronic condition; 43% cover Food and Drug Adminstration-approved weight loss medications and 28% may in the next one to two years.

Renee Rayburg, PSG’s vice president of specialty clinical consulting, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that the drugs have not been on the market long enough to provide any historical data.

“At this point, it is unclear if these medications will lead to sustained weight loss that delivers positive health benefits," Rayburg said. “From a health plan perspective, lifestyle resources (e.g., fitness programs incentives, lifestyle coaching) are not as highly utilized but are the most effective for weight loss management. These medications are indicated for chronic use, thus covering them is not a short-term cost, for example, as it is with bariatric surgery frequently covered by employers.”

Cost isn’t the only concern, however. Questions have always been raised about off-label use of medications and paying for lifestyle drugs, which health plans do not generally cover.

“The side effects of these drugs are not fully known, particularly longer-term ones, another reason payers may delay their decision-making process as regards to the current weight-loss drugs,” Rayburg said. “Right now, many payers are taking a ‘wait and see’ approach.”

Allen noted that some patients are seeing adverse effects when taking these drugs, such as vomiting and nausea, and are likely to regain weight after discontinuing the medications, which also leads to the hesitation.

Brent James, M.D., an expert on clinical quality improvement and patient safety, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that medicine has a long history of overreacting to a new drug and then quietly moving on when the full set of circumstances become known.

“A historical one is thalidomide,” James said. “I personally experienced, during my years of training in surgery, Halstead modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer, then high dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow transplant for metastatic breast cancer.”

James previously served as chief quality officer and executive director at the Institute for Healthcare Delivery Research at Intermountain Healthcare. Surgeons at Intermountain would sometimes use a special endoscopic device to close septal defects that allowed blood to move from the right side of the heart of the left, he said.

“We concluded that we should only allow these ‘off label’ uses—unproven technologies and approaches, in essence—in the context of a properly controlled trial,” James said. “Good medicine relies on solid evidence. Even if it seems like a good idea that should work, if the evidence isn’t there, then such a treatment should only proceed in a setting that can generate the essential evidence.”

Jeff Levin-Scherz, M.D., the population health leader for health and benefits in North America at Willis Towers Watson, noted that GLP-1 drugs have been in use since 2005.

“We know that they are safe, and that they’re safe for long-term use,” Levin-Scherz told Fierce Healthcare. “They are going to be in very high demand because there are a very large group of people who would benefit from them. The problem is that they cost too much and widespread coverage would indeed be very high. What we really need is to lower the unit cost for the drugs.”

He also said that while the Ozempic and other GLP-1 drugs fight diabetes, the American Medical Association named obesity a disease as well in 2013.

“I feel really strongly that no one should call these lifestyle drugs,” said Levin-Scherz. “We now understand obesity in a way that we didn’t 10 or 20 years ago, and we know obesity is a metabolic disease. Very, very few people can go from obese to normal weight with diet and exercise, and this is not simply a matter of lifestyle, or lack of willpower. It’s recognizing that once people are obese, the gut and the brain actually reset, and they make it very difficult for people to go back to normal weight.”

He predicted that new products will be produced over the next few years to compete with Ozempic and thereby lower the costs.

Meanwhile, payers have three choices, said Levin-Scherz. They can simply refuse to cover these medications, cover them following strict guidelines or cover them with the hope that they will eventually lead to lower healthcare costs down the line by decreasing the healthcare issues linked to obesity.

Peter Kongstvedt, M.D., a senior health policy faculty member in the Department of Health Administration and Policy at George Mason University, told Fierce Healthcare in an email that the evidence is there that these drugs work to help people lose weight.

“Based on what I’ve learned from disinterested medical education programs, semaglutide really does suppress appetite and usually leads to weight loss, sometimes dramatic, and because significantly excessive weight is associated with several serious chronic health conditions, I can’t really speak out against its use for that purpose though using it for primarily cosmetic reasons is irresponsible,” he said.

As for the price issue, Kongstvedt said that usually happens when a pharmaceutical protected by a patent has few competitors “because we allow a ‘free’ market in the U.S., unlike pretty much any other nation in the world.”

“Combined with our third-party payment system in which most people are protected from the impact of that pricing when a drug is covered, it provides a powerful motivation to drug manufacturers to jack prices up until they actually can look down upon the International Space Station,” Kongstvedt said.