The grading system for Medicare Advantage (MA) doesn’t give consumers the information they need to compare health plans, and that can result in poor outcomes, especially for more vulnerable enrollees, argue experts in JAMA Health Forum.

Co-authors Joan Teno, M.D., of the School of Public Health at Brown University, and Claire Ankuda, M.D., of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, liken the system to the tongue-in-cheek sign-off for the fictional town of Lake Wobegon on the radio program "Prairie Home Companion" in which “all the children are above average.”

That mathematical impossibility might serve as a good radio show gag, but many Medicare beneficiaries might not see the humor in having most MA plans rated above average, as is currently the case, the experts said.

“Our main point of the essay was that for certain quality measures healthcare is local, but the measures are capturing data from multiple states,” Teno told Fierce Healthcare.

In 2012, only 28% of MA enrollees were in plans that were deemed above average. By 2020, the share of MA enrollees in above average plans swelled to 83%. In addition, nearly 70% of Medicare-eligible individuals will be enrolled in MA plans by 2030.

The growth in the number of enrollees in above average MA plans did not result from quality improvement, argued Teno and Ankuda, but rather from consolidating the data of lower-rated and higher-rated health plans. That consolidation, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, resulted in 37% of Medicare beneficiaries being absorbed from plans with lower ratings into plans with higher ratings.

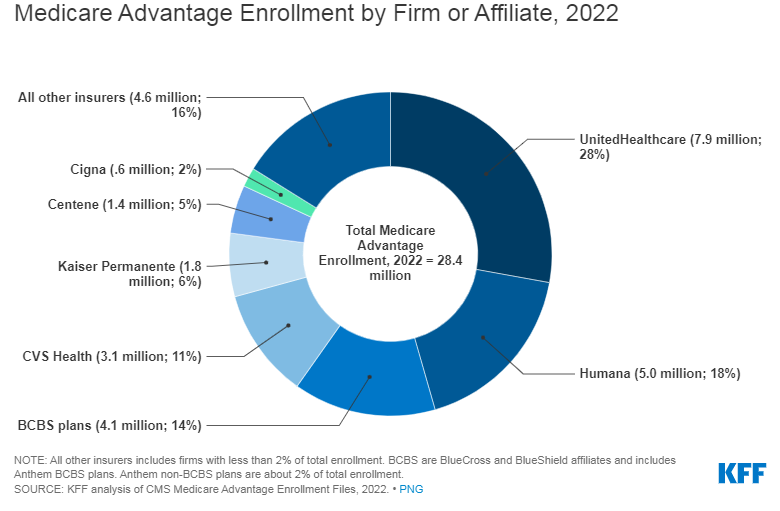

Teno and Ankuda said that MA quality has not been scrutinized closely enough and that consumers might be misled by the way information gets doled out. The main resource is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' (CMS') Medicare plan finder website, and the data come from the larger entity that might own an MA plan. UnitedHealthcare and Humana are the dominant players in the MA market, accounting for nearly half of enrollment.

The JAMA Health Forum article said, “CMS allows parent companies to consolidate plans into contracts as they wish, regardless of geography. For example, a UnitedHealthcare plan in Rhode Island with contract #H1944 is ranked based on data from 17 different plans across Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, Pennsylvania and New Hampshire. The current system of rating MA plans does not allow for meaningful comparisons.”

How MA plans receive bonuses and rebates is a complicated business. The Affordable Care Act that created the star rating system in 2010 stipulates that MA plans receiving a 4- or 5-star rating get a 5% or 10% increase in their benchmark, which is the maximum amount CMS will pay for an MA beneficiary. It’s a percentage of the estimated spending for fee-for-service Medicare enrollees in the same county. If the health plan spends below the benchmark, that money is returned to it in the form of a rebate.

In addition, health plans that receive a 4- or 5-star rating based on quality can also receive a bonus under the Quality Bonus Program (QBP). The benchmark is increased by 5% for most plans, but in counties with high MA enrollment, such as urban counties, the bonus can increase by 10%.

“In theory, the value-based financing of MA reverses the incentives from doing more to providing cost-effective, high-quality, and equitable care,” Teno and Ankuda wrote. “These same incentives could also motivate plans to achieve cost savings by just doing less: by denying beneficial treatments, requiring high co-payments for more costly services, or offering inadequate networks of clinicians and health care facilities.”

Teno told Fierce Healthcare that capturing quality care measures from multiple states cloaks lower performing health plans. For the seriously ill, local quality care measures—especially those individuals enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare—the Medicare plan finder website does not provide enough data to make a choice.

“It is time for independent review of the QBP with aim to provide actionable information for consumers,” Teno said.

For many years, low-performing MA plans found themselves in a Catch-22, because they could not get the bonus to initiate the improvements that they would need to make to eventually get that bonus. Teno said that although lower-rated plans risk losing their ability to enroll patients, she’s not convinced that lack of quality stems from lack of resources.

Peter Kongstvedt, M.D., is a nationally recognized authority on the healthcare industry and a senior health policy faculty member in the Department of Health Administration and Policy at George Mason University, says that the Catch-22 metaphor might be a bit of a stretch because “that makes it sound like a low performing plan is doomed. What potentially dooms them is not so much the bonus, but the fact that CMS removes low performing MA plans from its directories and if a beneficiary checks on it through CMS, they are told that the low performing plan doesn’t meet CMS’s standards for quality, and they may be better off elsewhere (though it does not prohibit members from signing up with that plan).”

Which perhaps begs the question: How many consumers actually compare MA plans?

“My guess is costs and networks are driving choices, until you are seriously ill,” said Teno. “Then the network and quality of the MA plan is really important.”