Employer-sponsored health insurance plans pay more—significantly more—to provide dialysis treatments for their beneficiaries than Medicare pays for its enrollees. Spending on dialysis for patients in commercial health plans in the first year after initiation of that treatment was $238,126 compared to the $80,509 spent on Medicare patients, according to a study in JAMA Network Open.

“This increase occurred across all spending categories (dialysis, non-dialysis outpatient, inpatient, physician services, and prescription drugs),” the study said. “Monthly patient out-of-pocket spending increased by $170 [with a 95% confidence interval range of $162-$178]. These spending increases occurred abruptly, beginning about 2 months before dialysis initiation, and remained increased for the subsequent 12 months.”

In this cohort study, researchers with Duke University examined data from the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) from 2012 to 2019. HCCI is a not-for-profit research institute founded by Aetna, Humana, Kaiser Permanente and Blue Health Intelligence. Medicare data were collected from the US Renal Data System. The data were analyzed from Aug. 27, 2021, to Aug. 18, 2022.

The study states that private insurers experienced “significant, sustained increases in spending when patients initiated dialysis” and “that proposed policies aimed at limiting the amount dialysis facilities charge private insurers and the enrollees has the potential to reduce health care spending in this high-cost population.”

Most of the plans were preferred provider organizations in companies that self-insure. Duke University researchers knew that they would probably find a cost gap when tallying what dialysis costs for enrollees in employer-sponsored health insurance plans compared to Medicare, but the size of that gap gave them pause.

Riley League, the study’s corresponding author, told Fierce Healthcare that “it’s not at all unusual for private insurers to pay higher prices than Medicare, but it is unusual for them to pay six times as much. It’s tough to say if this difference is because Medicare’s prices are very low or private prices are very high, but I’m inclined to think it’s the latter.”

The study found that spending at the 80th percentile for privately insured patients in the year following the first dialysis treatment was $343,082 compared to $122,348 for Medicare enrollees. At the 90th percentile the difference was $431,666 versus $164,709 for Medicare. At the 99th percentile the difference was $916,162 versus $308,314.

DaVita Inc. and Fresenius Medical Care control 72% of the kidney dialysis market, according to healthcare data aggregating organization HealthCare Appraisers. Such large market share may limit health plans’ ability to shop for best prices.

“Given how concentrated the provider side of the market is, I think that contributes quite a bit to the relatively high prices,” said League. “There are few other areas of healthcare where so few companies control so much of the national market.”

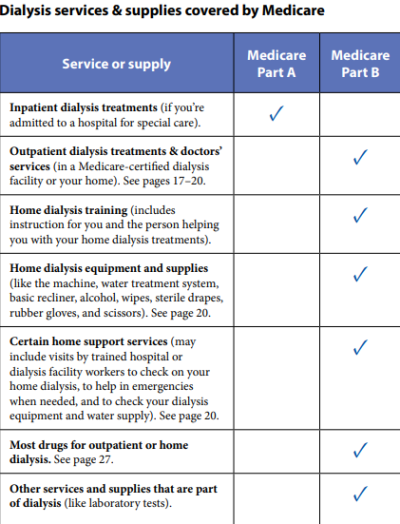

Patients on dialysis can qualify for Medicare coverage no matter what their age after a three-month waiting period. Patients in employer-sponsored health plans who begin dialysis can use Medicare for secondary coverage for 30 days but then can choose to make Medicare the primary coverage entity.

“Given the recent Supreme Court decision on the Medicare Secondary Payer Act, the cost differences between these programs remain important for policy makers,” the study found.

In Marietta Memorial Hospital Employee Health Benefit Plan v. DaVita Inc., DaVita argued that Marietta’s encouraging employees covered under its plan to switch to Medicare if they need dialysis violated the Medicare Secondary Payer Act.

The high court disagreed with DaVita’s argument that encouraging employees to switch to Medicare constitutes “differentiation,” or offering an inferior coverage option to some employees.

The high court countered that the applicable law “prohibits a plan from differentiating in benefits between individuals with and without end-stage renal disease. For example, a group health plan may not single out plan participants with end-stage renal disease by imposing higher deductibles on them, or by covering fewer services for them. If a plan does not differentiate in the benefits provided to individuals with and without end-stage renal disease, then a plan has not violated that statutory provision, and the differentiation inquiry ends there.”

The JAMA Network Open study states that the “ruling potentially undermines dialysis facilities’ abilities to charge high prices and may accelerate patients’ transitions to Medicare—an outcome that could result in lower health care spending given our findings.”

Here's more from our conversation with League:

Fierce Healthcare: Could you perhaps expound a bit more on the implications of the Supreme Court ruling?

Riley League: The Supreme Court decision has the potential to reduce healthcare spending on dialysis patients in two ways. The first is that it makes it easier to shift patients from private insurance to Medicare. Because private insurers pay so much more than Medicare, this would reduce total spending because there would be fewer patients in the high-cost bucket and more in the low-cost bucket.

The second is that it strengthens the negotiating position of private insurers, who may then be able to negotiate lower prices themselves. If private insurers previously believed that they had no choice but to cover dialysis care at any price and dialysis providers knew this, then dialysis providers could essentially charge whatever they wanted because they would know the insurers have to accept the deal. If the Supreme Court case makes it so that private insurers are more willing to fail to cover dialysis care, then private insurers will be in a better negotiating position because they could more credibly threaten to walk away from the bargaining table if the price dialysis providers are asking for is too high.

FH: What might be the ramifications in the real world?

RL: How things will play out in practice is murkier. Dialysis patients are a very sympathetic group, so it’s not clear to me how willing insurers will be to risk being seen as cutting their benefits and leaving them out in the cold. Another reason insurers may not negotiate aggressively is that most of them simply don’t insure that many enrollees that need dialysis, making it less worthwhile to risk bad press and exert a ton of negotiating effort.

Receiving dialysis care often makes it difficult to work, so many dialysis patients lose their employer-sponsored insurance and transition to Medicare before the end of the 30-month coordination period, meaning relatively few of them remain privately insured for an extended period. Finally, it’s not clear to me that before the Supreme Court case that private insurers believed they had absolutely no choice but to cover dialysis. The litigation we’ve seen over these issues (including Marietta v. DaVita and DaVita v. Amy’s Kitchen) suggests that at least some insurers were willing to push the envelope in negotiations with dialysis providers.

FH: This won’t be a major game changer?

RL: In theory the case could be a major game changer, but a few practical concerns make this less likely. It will all depend on how much the case changes the willingness of insurers to risk failing to cover dialysis and negotiate more aggressively. I should also note that this whole question may be moot because Congress may undo the court’s decision by mandating dialysis coverage. (See this proposed legislation.) I’m optimistic that the decision will lead to somewhat lower prices, but my personal opinion is that it is unlikely to result in sweeping changes to dialysis prices.

FH: Provisions of the Consolidated Appropriations Act that go into effect next year make companies that self-insure fiduciaries of the care their employees get. They’ll need to ensure good quality care at a fair price. Most of the employer-sponsored healthcare plans in your study were self-funded. Will this change that dynamic in any way?

RL: Like with the Supreme Court case, the impact of the Consolidated Appropriations Act will depend on how much it moves the needle on plans’ willingness to negotiate more aggressively and risk leaving dialysis as a non-covered service. My hunch is that this will change plans’ incentives less than the Supreme Court decision does because I would imagine it would be quite difficult for someone to sue a plan for paying the normal (if high) rate for dialysis as violating their fiduciary duty. I’m no lawyer though, so that prediction should be taken with a massive grain of salt.