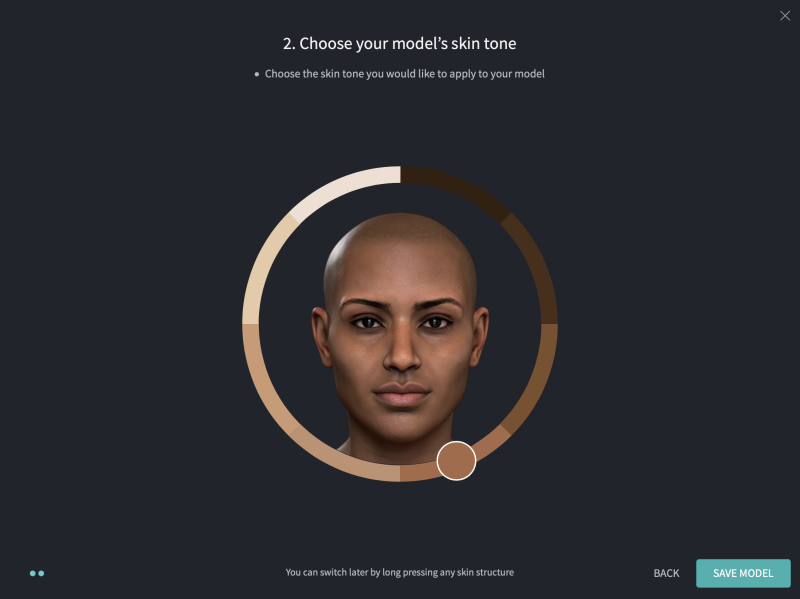

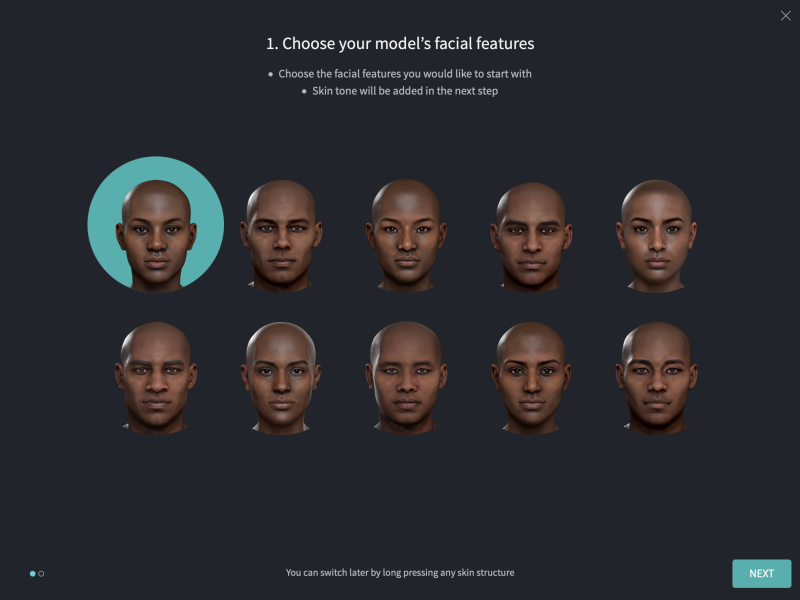

Elsevier’s updated 3D human anatomy model seeks to tie the tangible to the intangible—medical training tools to lingering racism within medicine. Complete Anatomy 2023 features the most expansive skin tone library available ever, according to the clinical practice content company.

Elsevier’s 3D4Medical team spent years consulting anthropologists, ancestral diversity experts, professors, students and 3D artists to create a wide range of skin tones and facial features. The Amsterdam-based company believes that inclusive models meeting students at their first day of medical school is an important step in addressing unconscious bias in future clinicians. Anatomy learning in the West has long defaulted to white models, said Irene Walsh, senior director of product and education design, in an interview with Fierce Healthcare.

“We're living in an era where we're starting to more and more realize that the system has taught us ways of interpreting the world around us rather than it being actually true,” Walsh said. “What we strive to do here is for students. On the very first day of their medical school training, they receive a resource giving them a variety of options. They will seek that variety the rest of their experience.”

Complete Anatomy by Elsevier has over 20 million downloads with 3.4 million active users. Over 500 institutions, universities and clinical organizations use the tool globally. The platform includes a “Gray’s Anatomy”-inspired atlas and dissection course, quizzes and videos. Complete Anatomy won the Apple Design Awards in 2016 and is the top-selling medical category app on iPad in the U.S.

Sections of the interface with toggles for skin tone and facial features are purposely unlabeled. Alan Delmar, product manager at Elsevier's 3D4 Medical, said simple moves like divorcing these features from language allow for a separation from outdated language and racial bias in medicine.

A 2018 study in the Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development found that less than 5% of images in general medical texts included dark skin tones. The same study emphasized that anti-racism work within medicine should start from the ground up with student training.

“Later down the line students get into clinical topology, dermatology—areas that we don't cover in a lot of detail—they'll hopefully start to request these kinds of resources,” Walsh said. “Even when they get to practice, it won't have been the first time that they see something, because they'll have experienced it from an early stage.”

Companies like VisualDx have tried to similarly disrupt the “default to whiteness” by creating collections of images of dermatological diseases on nonwhite bodies.

Cancerous melanomas, for example, present differently on different color skin tones. If a clinician fails to recognize skin cancers, time to diagnosis increases with increased chances of metastases. Black patients have lower rates of surviving skin cancer than their white counterparts.

Unlike melanoma, conditions like Lyme disease do not disproportionately affect people with lighter skin stones. An understanding of dermatological manifestations of the potentially neurologically devastating condition on all bodies must also be passed on to medical students, Delmar told Fierce Healthcare.

Racial bias among healthcare workers can be linked to poorer patient outcomes for people of color, a study published in the American Journal of Public Health found. Not only must racism be addressed in the diagnosis and treatment of patients but also how a patient is viewed from day one, Delmar said.

“There's an indirect effect to this, and there's a direct effect to this,” Delmar said. “Direct would be the lack of clinical images of melanoma on darker skin tones creating less informed healthcare professionals. They then may not be as quick to identify those diseases and appropriate time.”

“And indirect, we can find statistics everywhere. For example, women of Black ethnic backgrounds are 3.5 times more likely to die during childbirth than white women in the U.S. and 3.7 times more likely in the U.K. So that's something that might be a bit harder to attribute to the lack of medical images or ill-equipped health professionals, but we can see that it paints an overall picture of inferior healthcare that needs to be addressed.”

The racially inclusive model comes a year after the company released a 3D full female anatomy model with the hopes of disrupting the “default to male” model of medicine, according to Walsh. The model was the first ever 3D anatomy model to be female.

The team made the specific decision to configure the platform to default to female instead of male with the option of toggling to male at any time to counterbalance prevailing misogyny in medicine. The model includes subtle skeletal differences such as cranial features, pelvis shape and proportioned long bones.

Looking forward, the team is hoping to explore other models disrupting bias in medicine. Potential models Walsh is considering would involve intersex people and bodily changes over time, especially in females who may pass through quotidian but drastic anatomy changes throughout life like during pregnancy.